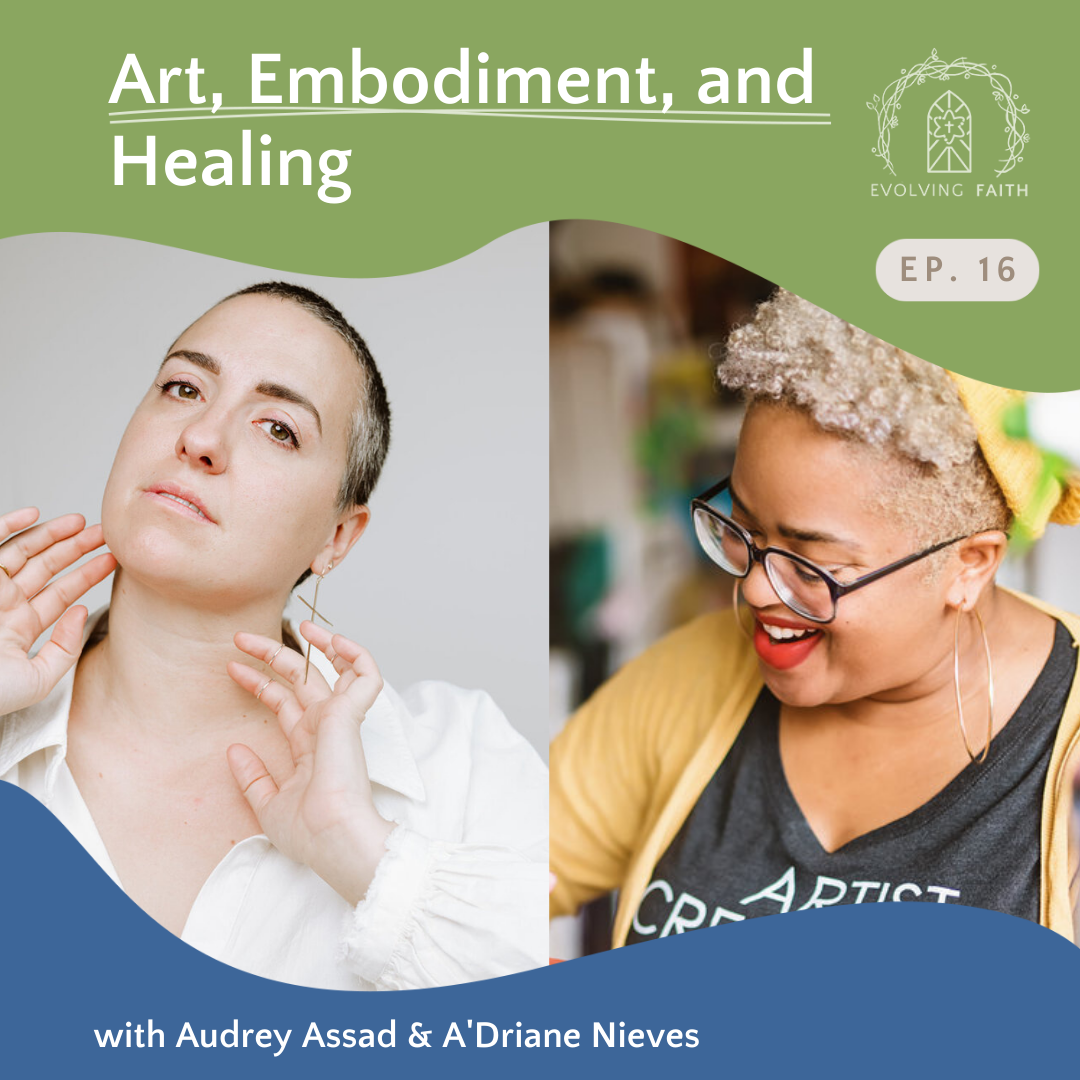

Ep. 16 Art, Embodiment, and Healing with Audrey Assad & A’Driane Nieves (E)

Hosted by Sarah Bessey and Jeff Chu

Featuring Audrey Assad and A’Driane Nieves

This week, we hear from two incredible artists: Audrey Assad and A’Driane Nieves as they engage with art, embodiment, healing, and an evolving faith. These talks remind us that artists bring to their work sorrows and joys, griefs and delights, which a canvas or a song can hint at. But there’s always more. Then Sarah and Jeff have a conversation about dancing, embodiment, creativity, and much more.

This episode has explicit language. Use discretion.

Now available and streaming wherever you listen to your podcasts.

P.S. Please note that some aspects of this episode do discuss themes of sexual abuse and violence so please listen only at your discretion. Look after yourselves, friends.

Listen & Subscribe

Show Notes

You can still register for Evolving Faith 2020 Live Virtual Conference even though it’s over. On-demand streaming of the conference is available to watch until April 1, 2021.

You can follow us on Twitter and Instagram. Join our podcast community over on Facebook, The Evolving Faith Podcast After-Party.

You can find Jeff Chu on Instagram and Twitter. You can also subscribe to his newsletter Notes of a Make-Believer Farmer at jeffchu.substack.com.

You can find Sarah Bessey on Instagram and Twitter. You can also subscribe to her newsletter Field Notes at sarahbessey.substack.com. Learn more about her books here.

Audrey Assad

A’Driane Nieves

Special thanks to Audrey Assad and Wes Willison for the music on this episode. And thanks as always to our producer, Lucy Huang.

“We create images. And they create us. We must create them again and again. And again. It is the work of an artist. What is art, but the making and the tearing down of images? We are iconoclasts.”

[IMAGE CONTENTS: First: Blue flourish at the bottom, green flourish at the top with the Evolving Faith logo. Text reads: Art, Embodiment, and Healing. The Evolving Faith Podcast Ep. 16 with Audrey Assad and A’Driane Nieves. Now Streaming. Remaining images are the same: white squares with a line drawing of an open book that has a tree growing out of the pages. Floating bubbles of green, maroon, and brown surround the bottom third. Text is as follows: 2. “I reject that my voice is worth less or must be silenced in order for me to display the glory of God. I reclaim the power of my voice even in this very moment.” - Audrey Assad 3. “We create images. And they create us. We must create them again and again. And again. It is the work of an artist. What is art, but the making and the tearing down of images? We are iconoclasts.” - Audrey Assad. 4. Our bodies need to heal, they need to move, they need to dance, our bodies need to love. Our bodies need to protest, our bodies need to march. loving my body isn't just about affection and feeling better. It is about justice, not only for myself as a victim of abuse, but for the bodies that are in danger today.” - Audrey Assad. 5. “You are a created being. That means you can create. All right. So all you have to do is just find the motive or the channel to express your creativity. - A’Driane Nieves. 6. What narratives are you listening to? What narratives are you telling yourself about yourself?” - A’Driane Nieves. 7. “And I'll tell you this, y'all ain't frail. Ain't nothing about you frail. The only thing frail is your ego. Okay. So my challenge to you is to break that ego, face yourself, find out what's inside.” - A’Driane Nieves. 8. “It’s also an act of rebellion and resistance to love your body, to treat your body with love and kindness and care.” - Sarah Bessey. 9. “God will meet with you in the boxes you create or are given but in God’s mercy, the box becomes too small for God.” - Sarah Bessey. 10. “Be authentic, be true to yourself and to your God, and be at once brave and tender in the face of a world that can be really harsh and unrelenting.” - Jeff Chu]

Transcript

SARAH: Hi, friends. Before this episode begins, one word of caution: Some of the themes in today’s episode may be triggering for some listeners. There are themes of sexual abuse and even violence, so look after yourselves and please listen at your discretion before we begin.

--

SARAH: Hi, friends. I’m Sarah Bessey.

JEFF: And I’m Jeff Chu. Welcome back to the Evolving Faith Podcast.

SARAH: This is a podcast for the wanderers, the misfits, and the spiritual refugees, to let you know you are not alone in the wilderness. We are all about hope, and we're here to point each other to God. No matter where you are on your journey, no matter what your story is, you are welcome! We're listening—to God, to one another, and to the world.

JEFF: The story of God is bigger, wider, more inclusive and welcoming, filled with more love, than we could ever imagine. There's room here for everyone.

SARAH: There is room here for you.

--

SARAH: All right, friends. Welcome back to the Evolving Faith Podcast! This is episode 16. Even though this episode is coming out after our 2020 gathering, we’re actually recording it ahead of time. So if you’re listening today after participating in the live virtual conference, welcome! We’re really glad you’re here. And we hope it went well? Who knows. I’m sure it was fine. I’m sure it was fine.

JEFF: Fine. That’s what we’re going for. That’s our bar: Fine!

SARAH: Anyway, today, we’ll be hearing from two amazing women: Audrey Assad and A’driane Nieves. Audrey is the singer-songwriter who performs our intro and outro music, “It Is Well With My Soul.” Audrey’s music reveals joy and heartbreak, pain and love. She’s based in Nashville and is the daughter of a Syrian refugee. She’s a writer and speaker and, no matter the medium, Audrey tells moving stories about art and faith, womanhood, justice, and wholeness. In addition to her work as a solo artist, she is also one-half of the alt-pop group LEVV and often writes and records with the worship collective The Porter’s Gate. Audrey was with us at the inaugural EF gathering back in 2018, which we’ll be listening to today, and we were delighted she was back with songs and stories at this year’s gathering.

JEFF: And then we’ll be hearing from A’driane Nieves. Addye is a disabled veteran of the United States Air Force, a multi-disciplinary abstract artist, a gallerist, an activist, and a speaker with a huge heart for serving others and social good. She is a mental-health advocate who lives with bipolar disorder. And she runs an online platform and mental health support group for women of color called the Tessera Collective. Addye believes that creating and viewing visual art that addresses difficult topics can serve as a catalyst for personal growth & social change and can also empower artists who are WoC to speak their truths. She “pushes womxn to transform the brokenness in their lives into power and beauty”—those are her words—and she works to amplify the voices and experiences of those marked as Other in society. Addye lives in New Jersey with her robotics-loving husband and three neurodivergent boys.

SARAH: Both Audrey and A’driane were part of a session at Evolving Faith that year that was centered on evolving faith and art, and they were alongside of Propaganda, who we listened to last week in Episode 15.

JEFF: Art, whether painting, as is Addye’s medium, or music, which is Audrey’s, can be powerful and transporting—and I know I’ve said this before on other episodes, but I also think it’s important to remember that we can tell stories in so many different ways. And these talks remind us that the artists are also more than their art. Addye and Audrey are complex and beautiful human beings who bring to their work sorrow and joy, grief and delight, which a canvas or a song can hint at. But there’s always more.

SARAH: Always. Always. So well said. I think that our spirituality is deeply connected to the art we make or experience. So friends, join us as we listen to Audrey and then A’Driane speaking at the very first Evolving Faith in 2018.

—

AUDREY ASSAD: Y'all, okay. Well, I've been a musician, and a songwriter and a performing artist and a producer for many years. Well, I say many—12 years. It's a lot for a 35-year-old. And along with that has come a fair amount of speaking. But as I was preparing for this talk, I realized that almost every time I ever speak in front of a room about anything, I tend to begin with some version of the line “I'm not really a speaker, but…” And I've been asking myself why that is, why I’ve felt the need to offer a disclaimer like that. I'm up here speaking, right?

I'm sure there are layers to this answer. But one thing that I know is that I am petrified of disappointing you. I am terrified of letting people down. And in fact, for much of my life, it has been the approval of others—the signing-off on my behavior and beliefs by other people—that has made me feel less terrified in what can seem like a brutal universe.

Another thing I know is that I was taught as a young woman that only men could teach, pray aloud, or read scripture in mixed-gender rooms. In fact, my spiritual home as a child taught me that a woman should not pray out loud in front of her own sons, if they were past the age of reason, as though she would be usurping their God-given male authority. And even as I have walked out and let go of so many of these ideas intellectually, I find that, in my body, there is still a little girl who believes that her biology disqualifies her from teaching, that her gifts and ideas, her strength and boldness, are a threat to the established order of things, and must therefore be kept silent. I reject that in Jesus’s name this morning.

[Applause] Thank you.

I reject. I reject that my voice is worth less or must be silenced in order for me to display the glory of God. I reclaim the power of my voice even in this very moment. And I speak these words over all of us today, words of a woman who herself bucked systems and stereotypes to become the first published woman writer in English: Julian of Norwich, who says, “Our Savior is our True Mother, out of whom we are endlessly born, in whom we are endlessly born, and out of whom we shall never come. We must be born again and again and again and again—not only our spirits, but our ideas, our bodies, and our images of God and ourselves.” So as I have undertaken the good work of rejecting spiritual and religious codependency and spiritual and religious Stockholm syndrome that characterized my spiritual life as a younger woman, I now joyfully and dare I say boldly take this opportunity gto tell you that I am Audrey Assad, the daughter of a Syrian refugee, artist, producer, writer, singer, speaker and teacher. [Applause] And thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

And I'm about to quote a white man— Sorry. I got other stuff coming.

“My idea of God is not a divine idea,” says C.S. Lewis. “It has to be shattered from time to time. He shatters it himself. He is the great iconoclast. Could we not almost say that this shattering is one of the marks of his presence?” Now I was raised in a small denomination called Plymouth Brethren. Have you? A few of you have heard of it? We are famous for our founder having first propagated the idea of the pre-tribulation rapture. You are welcome. There's a whole lot of trauma wrapped up in that whole thing. I like to describe it as what happens when the quietness of Quaker spirituality meets the aesthetic of fundamentalist Mormons. People, we did not have carpets, we did not have curtains. We did not have pictures on the bare brown walls of our buildings. But we did have women wearing long skirts and head coverings, and that is how we displayed God's glory to the world. Do you remember that passage in Paul's letter to the Corinthians? I'm going to read it in a room like this, I feel like that's a little controversial, but we're going to do it: “Now I praise you, brethren, that you remember me and all things and keep the traditions just as I delivered them to you. But I want you to know that the head of every man is Christ, the head of every woman is man. And the head of Christ is God. Every man praying or prophesying having his head covered dishonors his head. But every woman who prays or prophesies with her head uncovered dishonors her head for that as one in the same as if her head was shaved.” Heaven forbid. “For if a woman is not covered, let her also be shorn. But if it is shameful for a woman to be shorn or shave, let her be covered for a man, indeed ought not to cover his head since he is the image and glory of God but woman is the glory of man. For man is not from woman but woman from man nor was man created for the woman but woman for the man.”

Let me be very clear, I was created for no man. That story needs to be reimagined. And let me tell you one very tragic reason why. When I was 15 years old, I was babysitting three times a week for an elder at my church and his family. He was 40 or so. Wide frame, twinkling eyes. Everybody loved him. He was funny and charming and handsome and charismatic and I— I loved him. I gravitated towards him like a shy moth to a blazing light bulb, mostly because he seemed to see in me something that no one else could. We began attending this church when I was 13 years old. And before long, I realized that I was a favorite of this man's. And I felt so unnoticed and unseen in general in my home. So I unfolded like a flower underneath the warm light of what I believe to be kind and innocent attention.

This dynamic began to slowly escalate. And I found myself to be the center of this man's attention anytime I was in his presence, whether at home, at his house, or in the church building, and his commentary on me and my body evolved from what I viewed a simple and safe kindness to innuendos and solicitation. And any of you who have experienced sexual abuse of any kind will probably know what I mean when I say that my own reaction to this is the source of the most crippling shame I've ever experienced, since this man set his gaze and his eyes and his hands on me. And what do I mean when I say that? Part of the manipulation that abusers like this either learn or innately know how to wield is the power of shame in their victims. This man saw me, yes, not in a whole way or a healthy way. But he certainly was able to understand how starved for love and affection I was, and for noticing. And his noticing upon me, his gaze upon me, his hands on me were his predation on that lack and that void. The shame that I felt for so many years stems from my own sexual confusion during this experience, because I was at once incensed and frightened and aroused. And that's normal.

Side note: This experience, among others, including my rearing in an extremely misogynistic spiritual environment, wrote information into the neural pathways of my brain involving sex and shame that I am still fighting and spending hard-earned money on therapy to reverse.

One night I was babysitting when he and his wife were out to dinner. And when they returned, he said he would take me home. And on our way to the front door, he stopped me in the dark living room—his wife had gone into the bedroom to wash up and get ready for bed. He pulled me close in a hug and he told me how much he wished he could get even closer—I'll leave the details to your imaginations. And then he said, “Since I can't, here's 30 extra dollars,” and he slipped me some money. And I took it, but I didn't know what I was internalizing.

I look back on that moment, many years of therapy later, and I realize something now, which is that the ideas, the ideologies, and the anthropology that our communities espouse and create, they help us make images, images of ourselves, images of our neighbors of God. These pictures overlap and overlay and they create these composite images by which we make sense of our experiences and how we look at the world. I told other women at my church about this and they said, You just have to get out of his way. And you know what I heard: This is your fault. Another thing they told me is he's just like that, and everybody knows it. And I knew that they were right about that. This man was openly embracing and touching me not just in the darkness of his living room at night but in the broad daylight at church on Sunday. I felt sure in my gut of what all abuse victims seem to inherently know and be terrified to test, which is that I would not be believed. What images did those teachings about my womanhood and this man's abuse of my body help me to create? What images of my body lived in my imagination, then and for so many years afterwards? I'm going to give you one: Stumbling block.

Think of that: my beautiful, holy, wriggling perfect little body that came hurtling out of my mother's birth canal on July 1, 1983, reduced to “stumbling block,” by the images of woman that I was given, by the abuse that I experienced at the hands of a man who treated my body like it was indeed made for him. I repressed and I desexualized myself and I wore an invisible scarlet letter because everything they told me about my body had come true. I really was a woman, I realized, and I thought, “I am a problem. My body is dangerous. My body is a rebel just for existing. My body needs to be suppressed and covered and silenced. It is a stumbling block.” I began to live as though those images were reality. I repressed and I suppressed and I numbed and I shut off and silenced myself until I was a disembodied woman, as far away from at home in my body as I could possibly be.

We create images. And they create us. We must create them again and again and again. It is the work of an artist. What is art, but the making and the tearing down of images? We are iconoclasts, even as we make things, tweaking and re-examining our forms and our mediums and bleeding our pain and our vision out onto the pages of our journals, our sketchbooks, and our lives. Like Pete said yesterday in his amazing talk, the people of God are always reimagining God. We tear down the images that were constructed by us or constructed for us. And in doing it, we learn a better way to paint next time. We learn how to see the light better.

It's also the work of a child. And all children are artists. Have you ever watched a toddler knock down a block tower that you spent 10 minutes building when they begged you, Please play with me? You may have even been annoyed but maybe you also know that taking things apart is the only way that a baby learns how to put things together. As we deconstruct our images of ourselves and of God, we learn how to make better ones. This is the artist's way.

It wouldn't be a talk at Evolving Faith if I didn't talk about my evolving faith. So I never planned to be an unbeliever. “Believer” is how I defined myself. “Believer” is how I always saw myself and that was fortunate, because it was also the one thing I was taught I had to be if I wanted to avoid the eternal fiery pit of God's anger. Well, I never planned to stop being one but I did stop being one. Or at least it seemed like I had, because after all, I had stopped praying, I'd stopped going to church, reading books about doctrine, and writing worship songs—all of which had been such a part of how I felt safe and became at one point or another panic-inducing for me. There rose up in my days this wellspring of anxiety so crippling, it was exacerbated by my walking into a church building and I stopped doing all of it, because I had to. I had to learn how to breathe again. I had to learn how to function, and it all went out the window and I couldn't believe it. I thought, Am I really a full-time worship leader and devotional music artist, who doesn't go to church, pray, or read the Bible? Who can't even talk about God without an anxiety attack happening? I felt horribly disingenuous, but I also knew there was no way I would ever be back in the community of faith if I didn't stop being one for a while.

About four years ago, I became aware that my heart was more broken than I could ever have understood. I was manifesting PTSD symptoms. Years of talk therapy had not cured this. I've lived my whole life with something called religious OCD. Scrupulosity. It's a condition—Google it. It's like a hyper-examination of conscience. If you imagine the stereotype of OCD people is that they wash their hands constantly, well, I was constantly trying to cleanse my inner soul. I would spend three hours applying this blistering, legalistic salve to myself of praying the salvation prayer over and over and over hundreds of times and thinking, I don't think I meant it perfectly. I don't think I said it perfectly. I started having anxiety attacks in church. I started having anxiety attacks during sex. I would travel and speak and my thumbs were twitching maniacally. I couldn't play the piano. I had to cancel a whole season of shows. It felt like my whole foundation had been swallowed into a sinkhole. These questions were not fleeting. They were not satisfied by a quick scripture study or reading apologetics books or even by listening to the Liturgists podcast, which I love.

All I wanted was for God to speak up, show up, reveal God's self to me. Who are you? Are you even there? Despair became something that I had never been— a huge part of my life that I had never expected. How many people told you that God did not like you? Maybe they didn't say it with words. But maybe they said things like this: God had to put his wrath somewhere. Jesus took it so you didn't have to. And maybe like me, you heard, “God would have gladly struck you down if Jesus hadn't gotten in the way.” Maybe they said things like, God told Abraham to kill his only son, because he wanted to test Abraham's loyalty. And like me, you heard, “God is an abuser.”

The beliefs about ourselves and about God that many of us may have internalized from statements like these have been damaging. We have to do the work of healing each other and ourselves from the things that these images communicate to our hearts, the ways these images have made us in their own image. We have to do the work of healing each other and ourselves of self-loathing, of the unholy terror of a God that is petty and jealous and horribly fucking small.

I think that we need to discover a holy symbiosis between demolition and renovation. The divine flow of the Trinity, the endless river of breaking and remaking that is slowly but surely creating this world again and unbreaking every broken heart. Merton says this—Thomas Merton: “Therefore, there is only one problem on which all my existence, my peace and my happiness depend: to discover myself in discovering God. If I find him I will find myself and if I find my true self, I will find God.” We find ourselves, we find God, we find ourselves, we find God—symbiosis, demolition, renovation.

So how do we find God? This is the apex of this talk. Not really. But many of us in this room have despaired of God's existence. So original, and I have been one of them. Martin Luther King says, among many other prophetic and dangerous things, that the moral arc of the universe is long, but is bent towards justice. And I bring this quote up because I meditate on it every day to cure myself of despair. I want to throw back to some stuff that Sandra said, which maybe is cheating. But if we find ourselves paralyzed by despair, we need to move our bodies. We need to bend the arc with our bodies. You see, our white American religion, with its dogmas and addiction to superiority by doctrinal adherence, is missing something really large. We’re missing embodiment. I have news for this whole room: Our brains, our physical organs, my brain is a slimy, pulsating glob of gray matter and electricity. We are physical. And our bodies keep the score of spiritual abuse, of sexual abuse, of gaslighting. And I would even say that my body keeps the score of the atonement theory I was taught as a child, the deep self-hatred I internalized when I learned that God had to strike somebody down. And it should have been me. That pain lives knotted up and woven into the sinews and the tissues and the muscles of my body. For many of us in this room, our bodies keep the score of marginalization. Our bodies need to heal, they need to move, they need to dance. Our bodies need to love. Our bodies need to protest. Our bodies need to march. Loving my body isn't just about affection and feeling better. It is about justice, not only for myself as a victim of abuse, but for the bodies that are in danger today and every day, for the bodies that have been collateral damage of this administration and every administration before this one in this country.

My idea of God is not a divine idea. It has to be shattered from time to time. He shatters it himself. He's the great iconoclast. We destroy the images and we remake them. We make images and we make ourselves. So, as an artist, as a woman, iconoclasm is my reclamation of autonomy. When I was told that as a woman, I could not speak my prayers aloud in front of a body with a penis, iconoclasm as my adoption of the posture that as a woman my perspective on spirituality and God has weight and pith in equal proportion to those of the souls that animate male bodies. Iconoclasm is my dogged and unyielding insistence that when we preach about and evangelize for God whose existence and character are primarily shaped, interpreted, and documented by white men in power, we preach and evangelize a faith which is faltering, flaccid, and impotent.

Iconoclasm is rebirth. And today and every day, we must and we can be born again. Thank you.

--

AD

SARAH: Hi friends! Quick pop-in here just to remind you that if you attended Evolving Faith 2020 or even if you missed it, the goodness isn’t gone. You have access to the recording of the conference right up until April 1, 2021. You can watch it on your own time and at your own pace. So listen to incredible speakers like Audrey or our own very dear co-host Jeff along with me, Jen Hatmaker, Chanequa Walker-Barnes, Kate Bowler, Neichelle Guidry, Barbara Brown Taylor, Monica Coleman, Nadia Bolz-Weber, so many others. You don’t want to miss a single one. So go to evolvingfaith.com. The table in the wilderness is there for you still. Okay, back to the podcast.

--

A’DRIANE NIEVES: Wow. Well, how do you follow that? Right? We've got Propaganda. We've got Audrey Assad. And you're probably like, Who is this weird black woman standing onstage who wears clothes that don't match and blue lipstick? Who is she? Right? Um, well, I'm no Prop. I'm no Audrey. But my name is A’driane. You can call me Addye. My name, A’driane, actually derives from my great-grandmother's name. Her name was Addy Bell Lily. And so my name is A’driane and my great grandmother, she is here with us today. You can say hello, if you would like. Prince is also here. You can say hello to him. Okay? Which is awesome. Because I had no idea you were gonna like say that. So I was like, Oh, yeah, this is— he's here. Yeah, that's cool. He came to see us talk. That's awesome. And, you know, my great-grandmother is someone who I, over the years, have come to realize that she has been communicating with me and she has been channeling me and talking to me about the work that I'm here to do. Right? So I'm glad that she's here. Because if she was not here, I would be like dripping sweat from anxiety and would probably, like, run out of the room.

So, so you're probably wondering, like, Who is she? Why is she here? What is she going to talk to us about? Very good questions. Hopefully, by the end of this 18 minutes, I will have some answers for you. Because outside of that I'm pretty just as perplexed as you are. But I'm going to trust that Rachel and Sarah knew what they were doing when they invited me to come here. And, you know, signed y'all all up for this. So, good luck. Here we go.

Quick disclaimer: Yesterday's tone from my perspective was very much about tenderness. And meeting you where you're at. You know, an embrace. Some respite from whatever weariness and battles, you know, from the battles that you've been waging in your communities and your homes and your churches. Yesterday was about others seeing you. Right? Others seeing your wounds, others seeing your frailty, others seeing your vulnerability. Right? You guys with me? Okay. All right. You know, I come from black church—you gotta, I'm saying you gotta interact, gotta interact, even my artwork is call and response in nature. So you gotta— you gotta interact, okay?

But today, which I'm really glad that you scheduled that session, the way that you structured it, was brilliant, because today is not about being seen. It's not about others seeing you. Today is about you seeing yourself. Right? So I'm not really going to give you any relief from seeing yourself. I'm going to kind of do what we used to call in the military, some wall to wall counseling with you. Okay? All right. So, you know, I'm just going to go ahead and slam you right into the next wall. All right? You with me? All right. You've been warned.

Now, before I get into who I am right now, which might terrify some of you, I don't know, we'll get to that. And what I focus on in my art and how that can be applicable to what we're talking about yesterday and today regarding faith, let me tell you about who I've been: Bible nerd. Okay? A 13-year-old Bible nerd who was down with the DC Talk and wanted to be a youth pastor, marry Michael Tate, until I found out he was Republican and then that totally killed it for me. And work for race reconciliation, so that we could all be free at last. Okay? A Jesus freak, who along with a gang of other overzealous assholes, terrorized my junior high with smug evangelizing. Okay?

We were horrible.

If I ever blow up and get famous, I am praying my best friend in seventh grade who came out to me and I was like, “Oh my god, you're horrible.” I pray to God she never like finds me, or I pray that she does. So that way I can apologize to her. Her name was Amber. Okay?

Avid K-Love listener. Church usher. Church announcements reader. I mean, I had that down pat. Okay. Youth camp counselor, praise dancer, leader in young adult ministry. Pastor's kid, my mom is a pastor. She's a preacher. Thank God she's not watching this, because I'm going to say some things are probably going to like mortify her. I purposely did not give her the link to the livestream— they're not, no, you can't, you can't see this. Which means I told some lies. Sue me.

Now, so that's who I've been right? Different identities that I've worn right over the course of my life. Now let's jump into who I am right now. I'm a 35-year-old black queer woman who has survived childhood abuse, sexual assault, molestation, and has worked incredibly hard to process and outpace the continual impact that those experiences have on my body, and on my mind, and on my parenting and on my relationships. Okay?

I'm a wife married to a Puerto Rican man who is a futurist. He studies the emotional intelligence involved in AI and robotics. And he desires to have his brain and body preserved through cryonics upon his death, so that he can live forever, hopefully, I told him that he'd better not do that to me because if the technology does come out, and they are able to do that, and they bring me back, I will kill him. And then we will both be dead forever, which is what he does not want. Okay? He is also not a Christian. Okay? I'm a mother of three neuro-diverse Afro-Latino boys and a 10-month-old Labradoodle puppy who definitely needs Prozac. I'm a pastor's kid still, whose sister is also a Jehovah's Witness. I'm a pastor's kid whose friends are priestesses and priests in the Yoruba and Lukumi faiths, all right? I'm a pastor's kids whose friends are brujas and brujos— I got witches who are friends like very close friends and they're amazing people. And I have learned incredible things for them. So yes, you know, I got witches who are friends.Another reason why I'm glad my mom's not watching.

I’m a pastor's kid who speaks to my great-grandmother and to Prince like I've told you, I use tarot cards and candle magic. Okay? I read my horoscope daily. All right? It's like right after Instagram scrolling, I’m like, what does the daily horoscope say? Yeah, I'm a Sag. I'm a Cancer moon rising. You know, my moon is Gemini. Yeah, all that stuff. And I also pay very close attention to like the lunar cycle. Okay? I'm a very woo-woo mystical person is basically what I'm trying to get you to understand. Okay? So how did I go from overzealous, bigoted in some ways jerk, right? Very limited, narrow worldview. Right? convinced I was going to like, I don't know, like marry Michael Tate and live happily Christian ever after, right, to who I am now, right? How did I get to that? Well, I had some experiences that forced my faith to evolve. Right?

So how did that happen? Well, I had to do what Nina Simone says we have to do, and I had to burn some shit. Right? I had to get angry. You know. So when my oldest son's father looked at me after I told him I was pregnant, and said, I'm not going to be in our son’s lifeI had to get angry. Right? When I had to move back home with my parents with that son, after I was separated from the military, and I was basically homeless, and I had to move back in with one of my abusers, right, and I had to watch him sit in the front row in the church every Sunday, and be prayed for and heralded as a pillar in the church community, I had to get angry, right? I had to burn some shit. When I experienced postpartum depression and anxiety after the birth of my second son, I was terrified. Right? And then I got angry when I went to church who even had a therapist on staff, and no one saw that I was in crisis. And that I needed help. Not even the therapist who was on staff. Right?

When I got diagnosed with bipolar disorder about a year later, I had to realize that the things that I had been conditioned to believe, and the things that I had grown up with that were, you know, I thought were intrinsic to who I was, the practices and all those things, I had to get angry enough. And I had to care about myself enough, right? Because I was pretty much at the point where I was like, another two weeks, and I'm gonna end it, right. I had to get to the point to where I valued myself enough to say, Fuck this, I'm done. I'm gonna go over here, and I'm gonna find a way to live. Right?

So it's easy to say that, right? But I want to tell you something: In order to do that I had to face myself, right? James Baldwin says, who I love dearly, he said, Not everything that you face can be changed. But you can change what you face. Right? And so I had to do that. I had to start questioning everything that I had been taught, right? I grew up with a father who told me every day that I was evil, and God was going to kill me before I even reached age 20. Right? I grew up with a father who beat the hell out of me repeatedly. Okay? I grew up with a father who told me my mother didn't give a shit about me. Okay? I moved in with a stepfather who sexually assaulted and molested me, even though I was a teen— I was 16, 17, 18, 19. Okay? I grew up in a church that basically didn't care about any of that. Right? That basically told me that inherently, I was terrible, right? Basically reinforcing the same things that my own father had told me, right? That I didn't have any value, that I was bad, that I was evil, all of those things. So I had to question all of that. I had to look all of that in the face. I had to, I had to even look at my mom who's a pastor and be like, Oh, no, I don't know if this is, I don't know if this is the right thing for me. Right?

In 2011-2012, I transferred from community college to a school right outside of Langhorne, Pennsylvania, at the time it was called Philadelphia Biblical University. It's now called Cairn University. And that was another— I had all of these things kind of converging at the same time. I was recovering from postpartum depression and anxiety, I just been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, I basically told my family to eff off because I was like, I'm done. I don't want to be around this abuser. And I don't want to deal with your complicity around his actions. Like none of that, right? I had all these things converging. And here I was, a single mother of two kids, around all these 18-19-year-old kids and theology classes and stuff like that, right? And I was at this school, and I'm in theology class, and we're learning all these things, and we're having these debates. I'm having arguments. And that, my husband always, whenever he talks about me, he says, you know, there was A’driane before PBU and there was A’driane after PBU. Because the A’driane who came after PBU is who is standing in front of you right now. Right? And my husband always says, Man, I married such a sweet, kind, churchgoing girl. What happened to her? Where she go? And he'll be like, No, I know where she's at. She's somewhere walking around PBU lost, right? So yeah, that's basically what happened is I kind of had to, I had to confront myself, and I had to confront all the BS that had been fed into me and encoded into me, right? For years. So that's who I am now.

I'm an artist standing in front of you, telling you to do what Nina Simone says: You got to burn shit down. Okay? You've got to burn, whether through trauma or indoctrination or through conditioning, the frameworks and the constructs and the things that you have built around yourself mentally, okay, to keep yourself from exploring yourself, let alone the shit that is going on outside, you know, externally. You've got to get in inside here, you got to get deep, deep, deep down into your core, you got to examine the shit that's in there. Right? And this is not to, you know, I like what you said about, you know, like, beating white people and how they seem to like it, especially once they get woke, right? They're like, Yes, right, tell me how horrible I am! Tat's not the direction I'm trying to go in. And what I'm trying to get you to understand is that what you discover, when you do start doing that deep diving, start doing that work, it might not all be bad, right, or negative or doesn't have to be, right? But it might be some stuff that makes you uncomfortable. It might be some stuff that maybe you've been hiding from, it might be stuff that's been back in your subconscious tugging and pulling and nudging you trying to get your attention as you go about your day to day life experiencing people in different situations, to kind of illuminate some things about yourself you need to learn, right? Or some things about the world you need to learn.

I'm telling you that you've got to tear those things down. And you're probably like, okay, well, what the hell does that have to do with your art? I'll tell you. I am an intuitive visual artist. What does that mean? That means that I had to spend time, okay, or how did I get to being that? I had to spend time doing other practices that were non-Christian-related, right, like pulling tarot cards, right? I had to do that kind of a practice to reclaim the fact that intuition is what guides us. Right? Like, because I had been told that I can't trust what I think. I can't trust what I feel. I can't trust what I think I know. I can't trust what I've experienced. Right? So I had to go outside and practice this stuff. I was told it'll get you sent to hell, right? To reclaim that, and to be able to understand that I do have a voice— I can trust myself, I can trust my experiences, I can trust my thoughts. Right? You know, yes, I can have people like check me from time to time, which is necessary. I'm not saying that. But I can trust my intuition. So I use that in my artwork.

I started painting in 2012, at the recommendation of a therapist. I'd always been a writer, I'd always been doing like other performing arts, right? But I was the kid in seventh grade whose art teacher looked at my still-life drawing and was like, Nah, sis. That ain't you. You're on the debate team, you're in the theater club girl, you can orate like nobody's business, work with that. Leave the pencils and the paints alone. Okay, shout out to that dude. I'm up here now. But I started painting in 2012. And at first, it was just a way for me to kind of just quiet my own agitated state, because you know, I would experience hypomania, and that would leave me really anxious and frustrated. And I would just feel things so intensely. And so painting became this thing that I could use to kind of quiet my body and my mind and stop sweating profusely. And so what I, over time, what I started learning how to do is to kind of channel that intuition, right, that would that, as I confronted myself, as I asked myself questions, as I kind of forced myself to challenge what I thought I knew, intuition helped me start processing that through what I was putting on the canvas or on paper, right? And this is why I always encourage people. Everyone's like, Oh, I'm not creative. That's bullshit. Yes, you are. Right. You are a created being. That means you can, hello, create. Correct. All right? So all you have to do is just find the motive or the channel to express your creativity through. My husband's a coder. He tries to tell me all the time: Oh, I'm not a creative. Yes, you are! You build software systems. Are you crazy, right? Like, everything is creativity, you just have to find how to use it. So that's why I encourage people to do that. Because that's what happened for me, right. And so as I did that, and as I kind of reclaimed intuition, and found my voice and all of those things, what I started doing in my work is I decided that not only did I want to explore the themes of trauma and mental health and race, right? I wanted to create work that forces people to confront themselves, right? I wanted to create work that kind of holds up a mirror, even though it's abstract and not representational. I created an abstract on purpose. One, because I can't draw. Okay, but two, because I'm concerned about the internal processes that we experience throughout our lives as we experience different things. I'm concerned about how that impacts us. What does that look like on the inside? When we experience racism, when we experience sexism, when we experience sexual assault, when we experience anything positive, right? What impact does that have on us emotionally, physically? Right? How does that change us? And then how does that shape our identity over time? Right? How does that shape who not just who we are in the present but who we are in the future? Right? So real quickly, wrap this up. Has this made sense? Okay, good. That was my main concern is— it kind of makes sense. So, you know, we've been hearing a lot about deconstruction, reconstruction, right? This weekend? Well, yeah. How do you reconstruct? How do you deconstruct something? You got to do the work to kind of gotta tear shit down. You ever tried to tear down rocks or brick. It’s brutal work, right?

But it's worth doing, you have to do that. You have to be adaptive to change. One of the greatest lessons that I've had, is having to abandon everything that I thought I knew, you know, what taught me how to do that. Having neurodiverse children. Having two children who are autistic and having one child who has ADHD and anxiety. That forced me to abandon everything I thought I knew about parenting. Forced my husband to do the same thing, right? So you have to be open to doing and trying things that you've never tried or done before. Right? Even if you are terrified to do so, or someone's told you that it's wrong. You have to take the risk, again and again and again and again and again. You have to let each phase of growth that you experience as a result of taking that initial risk help you step off the ledge to take the next one. Right?

So what I want to ask you, what I want you to think about as you kind of as you go home, right, after you've kind of been beat up today, I want you to go home, and I want you to think about how your current trauma that you've been experiencing, right, the current battles, the challenges that you've currently been facing, how are they shaping you now but how are they also going to shape you in the future? In what ways are these things creating new molds for your identity to fill? What is laying the foundation for who you will be?

What narratives are you listening to? What narratives are you telling yourself about yourself? Are you listening to narratives that reinforce your feelings of victimhood, or ones that reinforce the necessity for vulnerability and honesty that trigger the contractions that birth growth, that provide the space for the healing process and ignites and cultivates actual transformation? It's important to face ourselves to look in the mirror and to get honest about what you feel in your body, in your heart, and think, right? It's very important to do that. And I'm telling you if I can do it, right, as a woman living with bipolar disorder, parenting three children, anxious-ridden dog, right, while living in Trump's America, okay, who has survived abuse of varying kinds? You can withstand this moment. Okay, I promise you you can. And I'll tell you this: y'all ain't frail. Ain't nothing about you frail. The only thing frail is your ego. Okay? So my challenge to you is to break that ego. Face yourself. Find out what's inside.

---

SARAH: Well, before we get started, I should mention that it is actually pouring rain here on the south coast of British Columbia, so I’m sorry if folks can hear the flood happening outside my office. It’s not as bad as your mic was a couple of episodes ago but still.

JEFF: Thanks for reminding us of that, Sarah.

SARAH: It just might be a thing! It might be a thing. All right. Okay, let’s talk about this.

There are so many good points in these two talks that I want to talk about and I already feel a little disappointed because I know we won’t be able to get to everything.

Listening to these two talks again reminded me of their unifying themes. You know, there’s art, there’s embodiment, there’s healing. Audrey talking about how in her body there is still that little girl who was taught that her biology disqualified her. That her body is dangerous and a stumbling block. And how living with that caused her to become disembodied. And Addye did the same thing, right? She turned to painting to begin to embody her own healing. And so they really are even in this moment iconoclasts, making and tearing down and embodying, just even in their talk.

JEFF: So you and Rachel really asked both of them to embody a kind of testimony on that stage, too, because you were inviting them to work in a different medium than they usually do.

SARAH: Right. And I was actually surprised by the testimony aspect that they brought to Evolving Faith. I think I expected maybe more of, you know, a “talk” about “art.” I’m wondering if people can actually hear me doing the air quotes with my hands right now. But instead they did exactly what they said— they embodied their story. They just owned it, and brought such vulnerability and honesty, and everything that makes them such incredible artists, they brought that to us—that whole story of who they are and how they create.

JEFF: Maybe it’s helpful for people to know that one of the traditions of Evolving Faith is that we don’t give the speakers parameters as to what they should or shouldn’t talk about. We just tell them that the gathering is about exactly what the title says: Evolving Faith. And then we might mention to them that they’re part of a session that has a theme, in this case, art, and that’s about it.

SARAH: When you say it like that, it makes me think it’s either a great act of faith on our part or an act of great foolishness.

JEFF: I think sometimes great faith does look to some like great foolishness. I think I’m okay with that. For now.

SARAH: Well, so far so good.

JEFF: So what we heard about bodies is interesting—that they keep the score of marginalization, which I feel in my bones, and they need to heal and they need to move and I am on board with that. But this is a really important quesiton. Do bodies really need to dance? I really don’t like dancing.

SARAH: You can dance with Fozzie.

JEFF: Fozzie isn’t much of a dancer either; he really just likes to chase rabbits and eat rabbit poop.

SARAH: I think that’s a form of embodiment...right?

JEFF: He’s living his truth.

SARAH: He’s living his truth. I read a book recently called Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle, by Emily and Amelia Nagoski. It’s just a phenomenal book about everything we’re talking about here. It’s about how reconnecting with our bodies - including every sort of body here - is key to embodiment and healing. As Audrey said, our bodies really do keep the score. That’s been a big part of my own healing as someone who lives with chronic illness. It’s helped me make peace with and love my body again.

JEFF: Loving my body as an act of justice—that’s something I am really thinking about, and the fact that I’m struggling even to talk about loving my body and to say this out loud, I think that says something. But how do we love our neighbors as ourselves if we don’t truly love ourselves? And how do we love and cherish and value others’ bodies if we don’t truly love and cherish and value our own? We are living in a time when it’s clearer than ever that some bodies are just not valued.

SARAH: Well, exactly. That’s perhaps why it’s also an act of rebellion and resistance to stubbornly love your body, to treat your body with love and kindness and care. Having to learn that after my car accident a few years ago and then these subsequent diagnoses with chronic pain and illness and these other things, I wrestled with my body even when it was fully abled and it wasn’t until I was on the other side of that story that I actually learned to truly embody this body, to truly love my body, even though it’s really different now.

I think even the invitation to creativity that Addye gave us is part of that prophetic act of loving our bodies. I love that she included all sorts of different types of creativity - painting like her or songwriting and singing like Audrey but there’s software coding. And that makes me wonder a bit even in terms of this conversation about the unsung acts of creativity and art that we just don’t “count” when we talk about creativity. And yet it can be so key to embodiment and to healing. And so I’m curous about some of the ways you explore creativity.

JEFF: This will be a surprise to nobody, but usually I feel super-awkward—both in mind and in body. And one of the only places where I think I feel free is the kitchen, and I mean that as a general concept, not the tiny, annoying kitchen I have here in Grand Rapids, which should really just be torn down. But I have this little notebook where I write down everything I’ve cooked for anyone, so that I don’t repeat dishes on the same guests too often, and when I’m sitting there, with the notebook, imagining a meal, I feel freedom to roam. And when I have my favorite knife in my hand and there’s space and light and everything is set up just so, I feel a fluidity in my movement that I can only describe as muscle memory that I must have inherited from my mom and my grandma. And people are like, How are you cooking six or seven dishes? But for Chinese people, that’s just dinner. How about you?

SARAH: Well, first things first: If you are keeping a notebook about repeating dishes, I’m just needing you to make a notation that I need you to revisit the brisket fried rice that you made for me that one time. I have never recovered. It was so good. All right, so writing is the obvious answer for me. I love to write. It is definitely the altar where I meet with God. I write way more than I publish or share. But I also find a lot of creativity in knitting. When I’m in a good writing stretch, I feel the same way I do when I’m knitting: this sense that you were talking about, of being at peace and fully present. I can find that space there between striving and resting where my mind is active and my hands are doing what they were meant to do and something that wasn’t there before is taking shape. I really love my work and I can get lost in it, and so when I finish a good stretch of writing, I do have this sense of feeling, you know, just spent and satisfied—and knitting can be the same way.

My husband Brian says that he feels that way when he’s working on projects around the house. He’s just one of those people who loves to lay floors, and cut baseboards, and build furniture and drywall. He loves how he feels when he’s doing it, like he’s at peace in his soul and his mind, because his hands are busy and he’s creating something good. I think that that act of creativity is as much of a gift as the product or the result maybe. JEFF: That makes sense.

SARAH: I’d love to hear from our listeners, maybe in the After Party some avenues of unexpected creativity where they feel embodied. We’ll have to have that conversation there. Addye did surprise me at the end of her talk because she did this really beautiful moment of inquiry. Rather than wrapping up with a tidy bow, she simply gives us good questions to ask ourselves. It’s like what the best kind of spiritual director does - or maybe the worst depending on how I feel with mine at any given moment. She asked us to ask ourselves - truly ask ourselves - what is laying the foundation of who you will be? And what narratives are you listening to? Her questions are, I think, real soulful inquiry for us. And it reminded me of what Audrey also said about how her questions weren’t fleeting or going to be satisfied by a particular book or scripture study or listening to a podcast— these questions aren’t externally a quick fix.

JEFF: What is it about our desire for the quick fix? And I say “our” there because, Sarah, you know how many times I’ve come to you and just said: “Please make it go away.” But life leaves us with these questions that linger—sometimes for years. And the work that both Addye and Audrey call us to is hard work and often slow work. It’s the work of relearning what your body is telling you and the work of learning to trust your God-given intuition and the work of discerning, as Addye says. You can’t proof-text your way to that kind of growth, and there are no silver bullets, not in self-help-book form or podcast form or pretty much any other form that I’ve discovered. And in some ways, maybe that work is meant to be lifelong work. We’re never finished, but maybe we can receive that as a gift, as room to grow and explore and make mistakes and accumulate wisdom, rather than as a life sentence.

SARAH: Well, exactly. I think that’s part of this journey of having an evolving faith that can be actually pretty frustrating at first and ends up being your joy. That proof-texts and podcasts don’t do the deep inner healing work - they can be tools and resources for f the work. Absolutely. Otherwise, why are we doing this? But this is perhaps even where my charismatic self shows up because I genuinely believe that is also the work of the Spirit. I think that’s where transformation and healing happens for us - it’s at that intersection of our choices, like Addye said, like who we listen to or what we learn or what we do or our habits and also of the Spirit. And I think God is engaged in that. It’s not one or the other. There’s a cooperative nature to this, I think.

JEFF: I love this idea that Audrey lifts up from C.S. Lewis of God as the great iconoclast and this notion that there’s something to be learned in the shattering of our images of God. Let me be clear: I wish it could happen without the trauma that Audrey experienced or that many others have experienced, myself included; I don’t believe in redemptive suffering. But I think there are some dangers in not recognizing that we do have a limited view, as humans, of who God is and what God might be doing in the world. So what I really hear is Audrey urging us to be humble and curious about God and God’s love rather than clinging to our fixed notions of God, and I think that as you say, as we grow and change in our understanding of God, as we meet the Holy Spirit, we are also transformed—I hope for the better.

SARAH: You know, a quote that actually led to me writing my last book was Meister Eckhart on that very thing. He’s this thirteenth century German mystic and he wrote this simple line, “God becomes, and God unbecomes.” And the unbecoming of God is actually what makes way for God. This is part of being born again and again and again. That God will meet with you in the boxes you create or are given but it’s in God’s mercy that that box does become too small for God.

JEFF: Both Addye and Audrey addressed a theme we’ve heard before, and this has to do with that box thing—ego, the desire for human approval, the fear of disappointing others. At the beginning of her talk, Audrey names that hunger, and at the end of her talk, Addye names the frail ego. And I don’t have anything particularly profound to say about this, except that I’m grateful for these reminders to be authentic, to be true to yourself and to your God, as your understanding of God and of yourself evolves, and to be at once brave and tender, especially in the face of a world that can be really harsh and unrelenting.

SARAH: I think you embody that wonderfully.

--

JEFF: You can find all of the links mentioned today, including info about Audrey and Addye and their beautiful work in the world as well as a full transcript in our show notes at evolvingfaith.com/podcast. You can sign up for my newsletter at jeffchu.substack.com and follow me on Instagram at @byjeffchu. The Evolving Faith Podcast is produced by us, Sarah Bessey and Jeff Chu, along with Lucy Huang. Thanks as always to Audrey Assad and Wes Willison for our music.

SARAH: You can find me at sarahbessey.com for all my social-media links, my newsletter, and of course my books. Join us next week for the first of two episodes about areas of representation where Evolving Faith fell short of our ideals at our first gathering and what we’re doing to begin to make things right. We’ll be hearing brand- new talks from three disabled people—Stephanie Tait, Raedorah Stewart, and Derrick Dawson—who will then join us for a roundtable conversation. Thanks for listening to this episode of the Evolving Faith Podcast, friends. And until next time, remember that you are loved.